How to fix the debates without cutting off candidates' mics

Stephen H. Provost

When I worked as a newspaper editor in Cambria, California, I was once offered a chance to moderate a political debate. I turned it down.

My reason was simple: The debate (actually a forum) was being sponsored by a group that had shown bias toward some candidates and against others, and I didn’t want to lend legitimacy to it. As it turned out, they recruited Ed Asner for the job, a move I reported in the newspaper. I was a lot more comfortable in that role.

Had it been sponsored by the League of Women Voters or some other nonaligned group, I might have accepted the assignment. After watching the first two national debates this campaign season, I’m convinced that would have been a bad idea for a very different reason.

I’m not a debate moderator.

None of the interrupting and talking over people that ruined the first presidential debate and was present in the Veep debate were present in the Cambria. That’s not because the participants were all in agreement — they were every bit as polarized on local issues as the two parties are nationally today. But none of these people was so full of their own self-importance that they felt entitled to interrupt or talk over others.

You know the saying about power corrupting? Yeah. That.

The Commission on Presidential Debates has chosen four moderators for this year’s series. They’re all journalists.

This is a mistake.

I’m not sure what sort of experience they have as debate moderators, although I do know Chris Wallace — who moderated the first debate — had moderated a debate between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton in 2016.

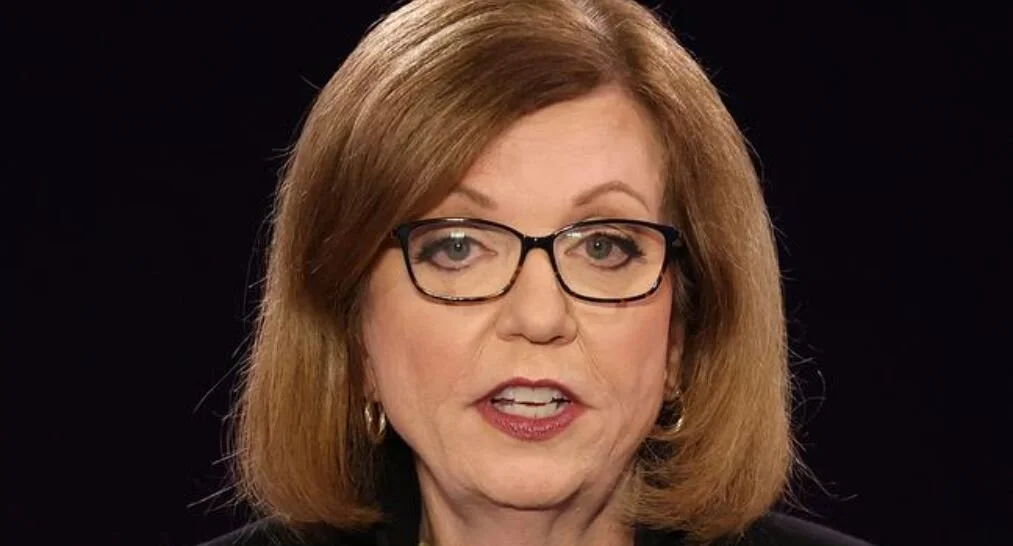

But neither Wallace in the first debate and nor Susan Page in the vice-presidential debate showed either the inclination or the ability to guide the discourse, which is what moderators are supposed to do. The fact is, both Wallace and Page earn their living as journalists, not by being involved in debates. Yet there are plenty of people who do regularly moderate college and high school debates across the country.

They have experience in this, so why not ask some of them to do it?

Journalists aren’t moderators

Asking journalists to moderate a presidential debate is like asking sportswriters (I used to be one of those, too) or ballplayers to umpire the World Series. Yes, they know the game, but no, they’re neither trained nor qualified to call balls and strikes. Even then, baseball umpires have a relatively easy job compared to, say, basketball referees. On the hardwood, refs have to deal with rapid-fire challenges and players who whine about every call they make.

The first (and perhaps only) presidential debate was something like that.

Neither Page nor Wallace knew a single basic technique that could have been used to rein in candidates without needing to shut off their mics. Both repeatedly admonished the candidates (primarily Donald Trump and Mike Pence) to stop talking once their time had expired; the candidates, however, just ignored them.

There’s a simple reason for this: They allowed the candidates to ignore their admonishment, effectively acting as though they were asking the candidates’ permission to enforce the rules. Instead of saying simply, “Thank you, Mr. Vice President” and stopping there, Page could have — and should have — immediately pivoted to Sen. Kamala Harris and said something like, “Senator, you have the floor.”

Then, if Pence had continued talking, she should have repeated that, more loudly and forcefully.

If Harris continued to talk, she should have done the same thing in the opposite direction.

But none of this would have been a problem if the commission had recruited actual debate moderators, rather than journalists, to oversee these debates. LeBron James might look like he knows better than the refs every time they make a call against him, but something tells me he wouldn’t want to exchange his current job for theirs, even if he were offered the same amount of money he’s paid now.

One thing’s for sure, he wouldn’t be as good at it as he is at being a player, or as the actual refs are at being refs.

It would be a fiasco.

Which is exactly what the first debate was. That’s not entirely Chris Wallace’s fault; it’s the fault of the commission for putting him in that position.