Please stop gaslighting perfectionists

Stephen H. Provost

“Gaslighting” has become a popular term, so much so that it’s likely overused. But I believe it applies in this case. One form of gaslighting involves blaming the victim: Making them feel like they’re responsible for your behavior.

This can cause people to question their perception of reality and wonder if they really are at fault.

Well-known examples of this dynamic include blaming a rape victim for her attacker’s actions by claiming she was dressed “provocatively,” and blaming a robbery victim for leaving valuables in plain sight.

Thought it’s not as obvious, society gaslights perfectionists all the time.

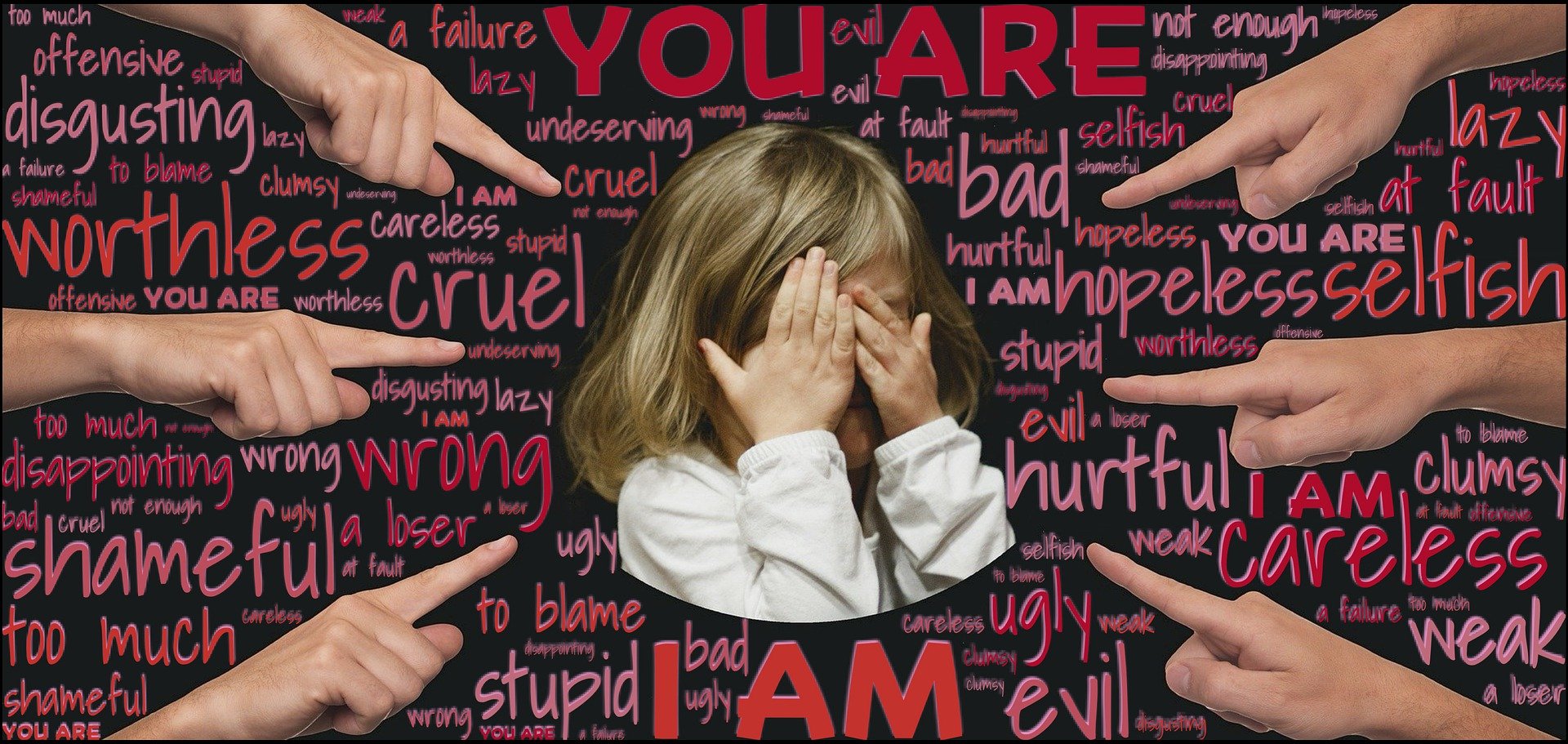

Have you ever felt like people are just lying in wait, ready to pounce on any mistake and tell you how flawed you are? (Often because they feel flawed themselves and need an excuse to feel superior.)

Have you ever been “canceled” for a single transgression and informed that it reflects some innate and irredeemable character flaw? Have little mistakes been blown out of proportion, as though they’re somehow going to usher in the apocalypse?

When you become self-protective, indecisive, or anxious, you may be told to “lighten up” or “chill out.” When you try harder to be perfect—so you don’t expose yourself to further criticism and ridicule—you might be accused of overreacting and “making too big a deal out of it.” Your critics may tell you not to worry so much about making a mistake; to just be yourself. But this probably feels like a trap, because you know that when you make the next mistake, they’ll be jumping down your throat yet again.

Here's the truth of the matter: Perfectionists are not born, we’re made. We’re intolerant of our own mistakes because society has conditioned us to be that way by being intolerant of us.

In fact, we’ve taken the initiative to blame ourselves in a desperate attempt to escape the blame of others.

The making of a perfectionist

The recipe for perfectionism often consists of two ingredients: a lack of tolerance and explosive anger. At least, that was true for me. I grew up with a father prone to occasional explosive outbursts. They were enough to make my mom retreat to the back of the house when he watched football games—at least those involving his favorite teams—and stay quiet until those games were finished.

I learned to mimic her behavior. If I was out of sight, I knew I wouldn’t be exposed to his anger. He wasn’t abusive toward me or Mom—not physically and not verbally, and he didn’t go around breaking things when he was mad (at least not on purpose). But the level of his anger was such that it left an indelible impression on me. Children often think they’re at fault for their parents’ anger or sadness, and while I never believed this consciously, I wonder if I didn’t, on some level, blame myself. It wasn’t rational, but kids often aren’t.

The second ingredient, a lack of tolerance, I learned from my peers. I was bullied, teased, and berated consistently during middle school and even into high school: It got so bad in 12th grade P.E. that I asked for (and received) a transfer out of the class so I could be a teacher’s aide for my favorite teacher, in algebra.

By then, academics had become my refuge from the bullies—and, happily, also a way to appease my father’s anger. As a professor, he valued academic success highly, and I know he was very proud that I was able to achieve a 3.93 grade-point average in college. It wasn’t perfect, but it was close. I might never get away from being teased for being shy or clumsy or failing to live up to a host of other societal expectations, but I had something many of them didn’t: I was smart enough to excel in school. It probably saved my life by salvaging a sense of self-worth that was circling the drain by the time I was 15.

What matters… and what doesn’t

Society’s lack of tolerance isn’t limited to big things like racism and sexism. It’s reflected every day in the value we (mis)place on silly annoyances that don’t matter a single bit in the bigger scheme of things.

When your wife is battling metastatic cancer, it puts things in perspective. And even so, I catch myself becoming frustrated at things that are so trivial I’ll have forgotten about them an hour later.

Society is very good at not only giving us permission, but encouraging and conditioning us to express indignation at these little things. We lament the fact that a driver neglected to use their turn signal—even though they’re three cars in front of us and changed lanes safely without it. We blast our roommate for putting the toilet paper on backward, even though they did so in the middle of the night when they were half-asleep. We berate our partner for forgetting to take the trash out. The list of hypotheticals goes on and on.

We even have the audacity to call upon people to do things they aren’t good at, then become irritated at them for… not being good at them.

Do any of these things really matter? Why do we allow ourselves to get so upset at things that either don’t affect us or won’t make a difference ten minutes later?

Because society encourages it, that’s why. It feeds us a diet of outrage and blame, and gets us so addicted to it that it becomes second nature. When I worked as a journalist, I was encouraged to put stories on the front page that elicited outrage from readers because that would stimulate engagement and sell papers. That’s not cynical on my part; it’s a fact. And I regret having been part of the process that reinforces the cycle of finger-pointing and alienation.

It's no mystery why we’ve become so immersed in a culture of tribalism and mutual recrimination.

Vulnerabilities

Why are some people more liable to be hurt by society’s blame game than others?

For one thing, we all experience different levels of vulnerability. Members of minority groups are targeted for who they are; they don’t even have the option of trying to meet society’s standards, because they never can. Society has made sure of that by disqualifying them based on their identity. Perfectionism won’t do them any good.

But there are subtler forms of blame that give others hope that, if they’re somehow good enough, society will accept them—even though society is determined not to. Some people are castigated for being shy. Others for being forgetful. (I’ve fallen into both categories.) Maybe they’ve forgotten something because they aren’t good at multitasking and they’re focused on something else. Maybe they have different priorities, like thinking about the plot for their next novel or trying to find the next scientific breakthrough. Perhaps they’re even in the early stages of dementia.

All too often, society doesn’t care about the reasons. People only care about the fact that they’ve been “put out” and/or want an excuse to blame someone for something. Ironically, many of those most intent on casting blame are perfectionists themselves seeking to validate their own self-worth by micromanaging and condemning others.

Responses

There aren’t many defenses against being hurt this way. One is to stop caring what others think and treat their feelings as though they don’t matter. Others are perfectionism and avoidance. We perfectionists try to be perfect so we won’t be ridiculed, and when that doesn’t work, we seek to avoid the source of the criticism altogether. We either isolate ourselves or make sure we don’t even put ourselves in a position to make the same mistake again.

Warning: blunt example ahead.

Decades ago, I started sitting down whenever I used the bathroom because I recognized my own tendency to get caught up in my own thoughts. I knew I would forget to put the seat down every now and then, and I didn’t want to be accused of being inconsiderate. So I found a way to keep that from happening. It worked.

But of course, you can’t always avoid making mistakes. So I’ve also become something of a recluse, because I’m tired of exposing myself to intolerant people intent on finding reasons to condemn me. To make me think I’m not good enough, when I know that’s not the case. I know their behavior toward me isn’t personal—they probably think the same thing about everyone else—but that doesn’t make it any less toxic or any easier to take if you’re a perfectionist.

If, like me, you were exposed to explosive anger as a child, you may have learned to simply shut your mouth in the face of criticism and bottle everything up. How does a 5-year-old kid challenge a 6-foot-8 professor with a booming voice who knows he’s right? He doesn’t. He learns his place, and he stays there—even if it’s not really where he belongs. (Full disclosure: I loved my father. He had some flaws, such as his anger, but he was on balance a very thoughtful man who taught me a lot and treated my mom like she was the treasure she was. Like everyone else, he wasn’t perfect, and I never expected him to be.)

There’s a saying that anger is merely an expression of hurt. Well, we get angry too, but we seldom express it for two reasons. First, there may be too much at stake (we don’t have the power in a given situation), and second, we don’t want to exhibit the very sort of behavior that hurt us.

So we become anxious and depressed. Those conditions are often merely expressions of anger we can’t let out, which in turn is an expression of the sadness we felt at being hurt. In a very real sense, depression is sadness compounded upon itself, with anger as a silent intermediary.

If all this sounds, well, very depressing, it can be. Perfectionists don’t like being this way, and we certainly weren’t born like this, so please have some compassion and don’t blame us for working to protect ourselves by trying harder. I’m not ashamed of myself for trying. Some people don’t try at all. And if I were to stop trying, it would mean depression had won. I don’t intend to let that happen. I work to stay positive about myself. And when it comes right down to it, I’d much rather be a perfectionist than someone who passes the buck by gaslighting and blaming victims.

I simply refuse to go there.

Stephen H. Provost is the author of more than 50 works of fiction and nonfiction. His latest book, Sierra Highway, was published in September 2023.