It was easy when I lived in California. I wrote books about highways marked by straightforward numbers (Highway 99 and Highway 101). No controversy there. They had names, too, but “El Camino Real,” “Golden State Boulevard” and “The Hollywood Freeway” are pretty benign.

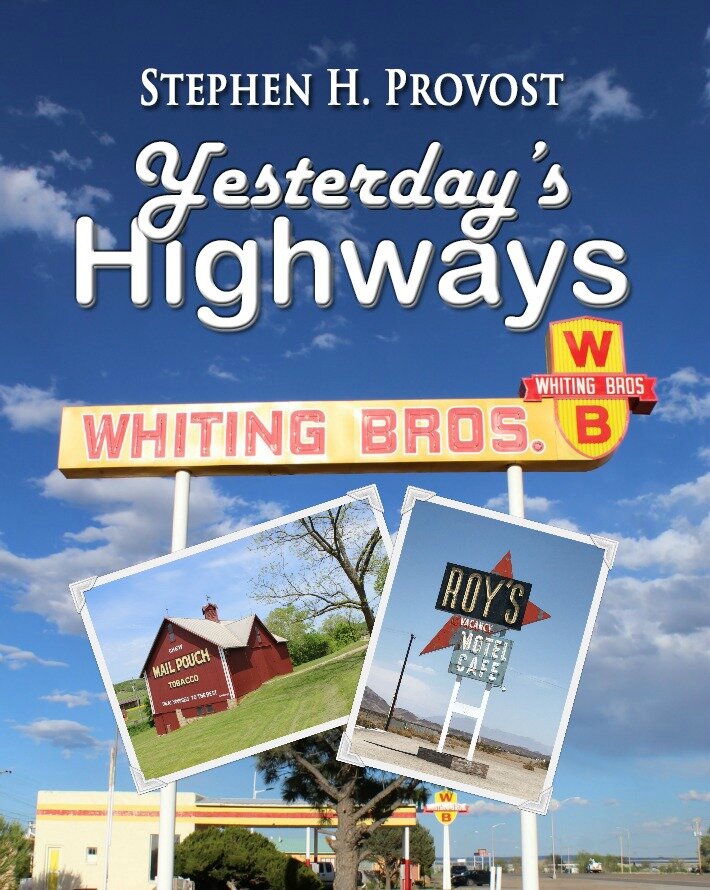

Then, I moved to the South, and I wanted to keep writing about highways. My first offering, Yesterday’s Highways, dealt mostly with numbered roads on the federal highway system, like Route 66. But before those roads had numbers, they had names. Nothing else, just names.

They were called auto trails, privately funded highways that were part gravel, part pavement and part dirt that crisscrossed the country in the early years of the 20th century. They’re the subject of my forthcoming work, America’s First Highways.

The highway builders promoted them by naming them for larger-than-life figures like Lincoln and Roosevelt, Jackson and Jefferson. Or for geography, adopting names like Yellowstone and Pikes Peak.

In the South, however, highway builders paid tribute to figures like Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee, “heroes” of the Confederacy. I put “heroes” in quotes, because I can’t fathom ever applying such a term to men who fought a bloody war for a system of government that brutally enslaved human beings.

When I shot the cover art for my book Martinsville Memories, depicting this Southern town’s historic courthouse, I purposely excluded the Confederate monument on the front lawn. As I’ve written in the past, I don’t believe the Confederacy should be celebrated.

Yet I did want to celebrate the auto trails that bore the names of these men. The question was how to do so without celebrating the men themselves. For one thing, I view the monuments alongside these roads more as tributes to the roads’ builders than to slavery.

Carl Fisher, a man who built the Indianapolis Motor Speedway and developed Miami Beach, would have been an impressive figure even if he hadn’t started the two most significant auto trails: the Lincoln and Dixie highways. The names would seem an interesting contrast. The first, running east to west was named for “The Great Emancipator,” while the second, oriented north and south, bore a name many associate with the Confederacy.

“Dixie” was, after all, the title of the most famous Confederate anthem, often performed my minstrels in blackface. Yet Lincoln himself deemed it “one of the best tunes” he’d ever heard, and the term “Dixie” started off as a geographical reference to the Mason-Dixon Line separating Pennsylvania and Maryland. Many today still view it in purely geographic terms, and Fisher’s group saw their Dixie Highway as a bridge to tie the nation back together after the Civil War.

Not that Fisher himself was a saint, by any means. He was sometimes a drunk who, at the age of 35, ditched his fiancée of nine years to marry a 15-year-old girl. And his main purpose in building the road was to give northerners a way to reach his resorts in Miami Beach. It was, for him, a money-making proposition.

When writing about these old roads, it’s impossible to simply ignore their names — even though many conveniently ignore that the Jefferson Highway’s namesake was a slaveholder, too. (A visit to Monticello, Thomas Jefferson’s estate, can be an eye-opener for its tour of the slave quarters and is highly recommended.)

I’m happy that the Jefferson Davis Highway has been renamed the Richmond Highway through part of Virginia, and it’s fine with me that a portion of the Dixie Highway through Florida is now named for Barack Obama. Another president’s name on an old auto trail is a perfect fit. Plus, I have to say I enjoy the fact that it must have galled Lee Highway boosters that their road passed by a historic African-American church in Marion, Va.

But history is seldom simple. I don’t believe the names of these roads should obscure their importance to the development of our nation’s road system. Nor do I believe that huge turning point in our history should overlook the fact that highways in the South were often built by chain gangs of inmates — most of whom were black and many of whom were unjustly imprisoned.

History should shine a light on virtuous and vile deeds alike, so we can know how to replicate the former and avoid repeating the latter.

That’s what I hope my writing does. It can be a difficult line to walk, but it’s always a worthy goal, and one I intend to keep pursuing.

Photo: An exit for U.S. Highway 11, aka the Lee Highway, in western Virginia (author photo)